Transnational wind energy projects threaten Sámi culture

Mostly the indigenous European Sámi people are reserved and peaceful and are not known to like to protest. So it means something when, in 2023, a large group of young people in Sámi costume marches through Oslo for days, chanting protest yoiks and besieging 11 ministries, including the Ministry of Energy for 92 hours until it was evacuated.

One year later, in Oslo Tingrett we observe this situation: around 18 young people, mostly in Sámi costume, sit in two rows in front of the judge and the public prosecutor and explain why they are not paying the fines for the police eviction from 2023. They are doing this individually, but have a common strategy: this trial should be conducted politically, because their motive for the sit-ins at the Oslo ministries was political.

The government should finally respond to a Supreme Court ruling from 2021 and put an end to the violation of Sámi human rights.

The atmosphere in the hall is emotional, the days-long strain is great and some of the young activists cry during their personal statements.

The Sámi protests were followed closely in Norway and also made international headlines as the „Fosen case“. The activists in Oslo had shown solidarity with Sámi reindeer herders from the Fosen peninsula, on whose winter pastures two large wind parks had been built. The reindeer herders were against the construction of the turbines and had been arguing in the courts since the concession was awarded in 2013.

The Norwegian Supreme Court finally ruled in 2021 that the construction of the turbines violated the Sámi’s human rights to practice their culture and that the state concession was invalid.

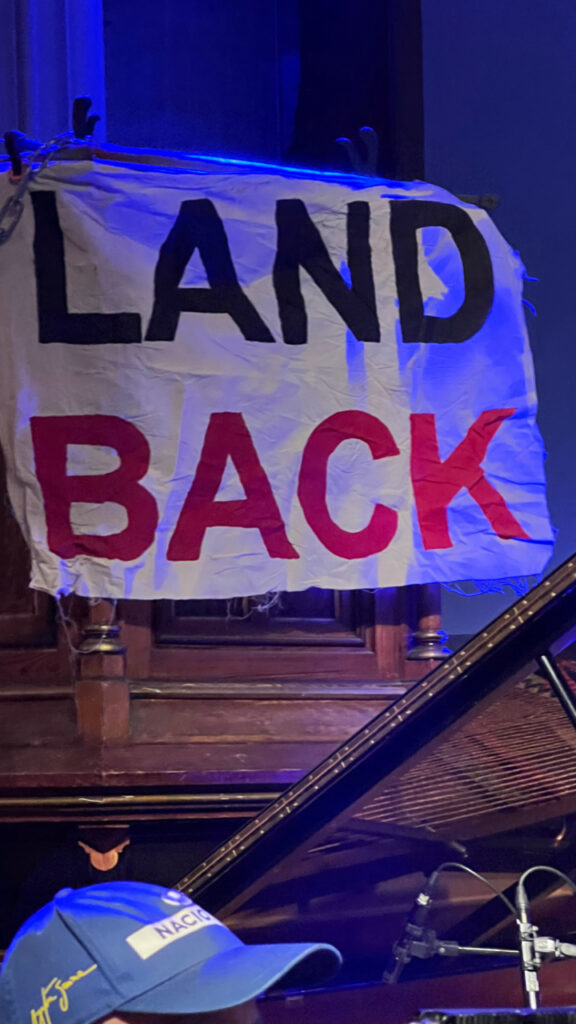

Now the reindeer herders demanded „Land Back“ and the demolition of the wind farms, but nothing happened, the wind turbines continued to turn and the reindeer herders of Fosen were rid of their winter pastures. Even Greta Thunberg showed solidarity. She is not an avowed opponent of wind power, but as a Swede she has her own „history“ with Europe’s indigenous people.

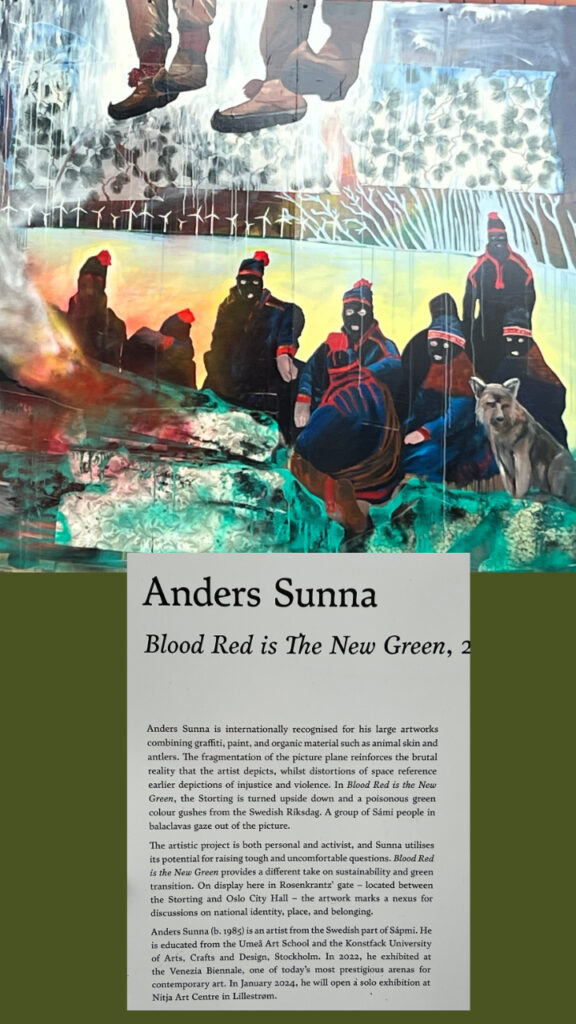

As nomads, all Sámi have historical conflicts with the so-called cultural peoples of the nation states and the Sámi living in Sweden have been harassed even more than those in Norway. In the streets of Oslo, we came across a mural by the Sámi painter Anders Sunna, which tells a dramatic story of the Swedish Sápmi.

The Fosen case therefore also became a „Sápmi“ case.

Sápmi is the original habitat of the Sámi in Sweden, Norway, Finland and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. For the traditionally living and farming Sámi, national borders are artificial structures that sabotage their nomadic way of life. And today, the threat to their reindeer herding from wind turbines is compounded by the climate crisis.

The interdisciplinary researcher Susanne Normann, who combines community psychology and cultural psychology to focus on „climate psychology“, calls this a „double burden“.

On the one hand, there are the energy projects „branded“ as green, which are stealing territory from the Sámi. On the other hand, the reindeer herders are experiencing an aggravated situation due to extremely changeable weather in winter, for example. When thaws are quickly followed by sub-zero temperatures and the animals are cut off from their food by the icy conditions, their nomadic flexibility in search of pastures is blocked by the energy projects.

The cultural history of the Sámi could also be understood in Arctic contexts instead of national classifications. For some years now, attempts have been made throughout the Arctic to overcome the collective trauma caused by forced assimilation, the suppression of culture and the banning of their own language through truth and reconciliation commissions. This also applies to the Sámi populations in Scandinavia.

But „reconciliation“ is not easy if the disregard for rights and thus, as many Sámi see it, the suppression of culture continues.

Reindeer herders have to defend their rights in complicated and expensive lawsuits. When the Sámi dispossessed in Fosen find out that the „green“ electricity produced there by Germans and Swiss is to be used to electrify Norwegian oil production, the trust the Sámi have built up in the reconciliation process is once again called into question.

Silje Karine Muotka, the president of the Sámetinget, was also at the trial in Oslo. She says:

The Sámirat and the Sámetinget, based in Karasjok (founded in 1989), are themselves the result of energy struggles. When the Norwegian government wanted to build a dam for a hydroelectric power plant in the Alta Valley and flood an entire Sámi village in the process, the Sámi fought back. The first major Sámi environmental movement in the 1980s came into sharp conflict with the authorities and in the end the dam was built.

But the Alta conflict was the „Urszene“ of a modern Sámi protest culture and stands for a new Sámi self-confidence.

Was it a coincidence that a feature film about the Alta conflict was released in Norwegian cinemas just as the Fosen protests began in Oslo? The film certainly had consequences, as the protests now had the backing of the Norwegian public. And one face, that is Ella Marie Isaksen. She plays the leading role of a rebellious young Sámi activist.

Ella Marie Isaksen was already famous, she has transformed the traditional form of yoiking into a kind of pop art yoiking and has had great success with it. She is also a well-known environmental activist in Norway.

In August 2021, she and other Sámi and young conservationists were able to stop a copper mine on the ecologically vulnerable Reppar Fjord and in Oslo, the 25-year-old was at the forefront of the protests against the government.

Ella Marie Isaksen puts her finger in the wound:

In the end, the government had to respond to the protests in Oslo, promising better participation of the Sámi in the planning of future wind energy projects. However, the public prosecutor’s office has appealed against the acquittal of the activists at Oslo Tingrett (in May 2024).

The government and wind energy operators emphasize that there is no precedent, only the „individual case of Fosen“, from which the appropriate lessons will be learned. Climate psychologist Susanne Normann, on the other hand, points out that there are many disputes, we should just take a look around the north.

And we find what we are looking for in the tranquil village of Mosjöen in northern Norway.

Here the Hamburg-based investment fund Aquila Capital is financing the Öyfjellet Vindpark with 72 wind turbines up to 150 meters high, whose electricity will be supplied exclusively to Alcoa’s aluminium factory, which has been located there since the 1960s.

However, the wind farm disturbs the annual migration of the reindeer herds in the district. To ensure that turbine operation is not interrupted for too long or at all, the district’s reindeer herders are being advised to use industrial methods, such as helicopter drifting or transportation in trucks. The reindeer herders, on the other hand, want to stick to their tradition and move the animals slowly and at their own pace through the area.

And again the Sámi end up in court.

For the environmental movement Motvind (Headwind), the additional wind power raises other economic problems: Until now, industry here has lived off cheap hydroelectricity. If additional demand for wind energy is created, this will lead to additional infrastructure costs and higher prices. The Mosjöen site would then no longer be profitable.

In the case of Mosjöen, the question of cultural reconciliation also arises again. The local pastor and supporter of ecotheological approaches also has something to say about this:

„We got the Truth and Reconciliation Commission last year, in June last year, exactly one year ago, and we now know for a fact that the church was the extended arm of the state in the Norwegianization of the Sámi people. So it’s pretty important that we get back on the right side and that we apologize.“