A LECTURE FROM AMSTERDAM

At the beginning of July, I was in Amsterdam conducting research on Dutch colonial history. This topic is something that has interested me and my partner for quite some time, namely European colonialism and the role of Christian missions. Since Jane is Danish and we have been exploring the periphery of the former empire for some time, we came across the Herrnhut missionaries, who were very active in the Danish Empire and, as we saw after our last broadcasts about Herrnhut and its historical legacy, also in the Dutch colonies.

So at some point, Amsterdam, the metropolis of European colonialism, was bound to be next, and Keti Koti was the perfect occasion. Keti Koti, Broken Chains, an anniversary commemorating the abolition of slavery on July 1, 1863/73, has been commemorated every year since then in the Netherlands and its former colonies. Whether or not it is celebrated depends on the intentions of those involved. A Surinamese sister of the Moravian Church in Amsterdam, for example, said there was nothing to celebrate, even though her congregation had just held a Keti Koti service in the Konigskirke. For her, the day is much more a moment of mourning and quiet remembrance of the suffering endured by her ancestors.

At noon, we attended the ceremony at the central monument in Oosterpark, where Keti Koti was celebrated in an official ceremony attended by the prime minister and the mayor of Amsterdam, as well as numerous speakers and activists from Amsterdam’s postcolonial community, which within a few years has built an incredible movement for public Reflection on colonial history has reached a new level. In addition, a woman performed a Winti ritual in accordance with ancient Afro-Surinamese tradition. I am not sure if she is considered a Winti priestess.

In any case, the ceremony was moving, and as I stood there with my parasol, two microphones, and cameras on the press platform in the sun on July 1 at 36°C (Jane was in the Konigskirke with the Surinamese Herrnhuters at the same time), I also found the honor guard standing at attention quite moving, dozens of people in full uniform, at least they were able to take turns from time to time, while I had to remain at the top in a press zone that was, incidentally, quite far from the action.

But it was worth it, because afterwards I got a great interview with Maurice San A Jong, who is currently researching the perspective of enslaved people on the Herrnhut mission. We will comment in detail on the content of this oral history in upcoming articles for Deutschlandfunk. For example a first program, 8 minutes here:

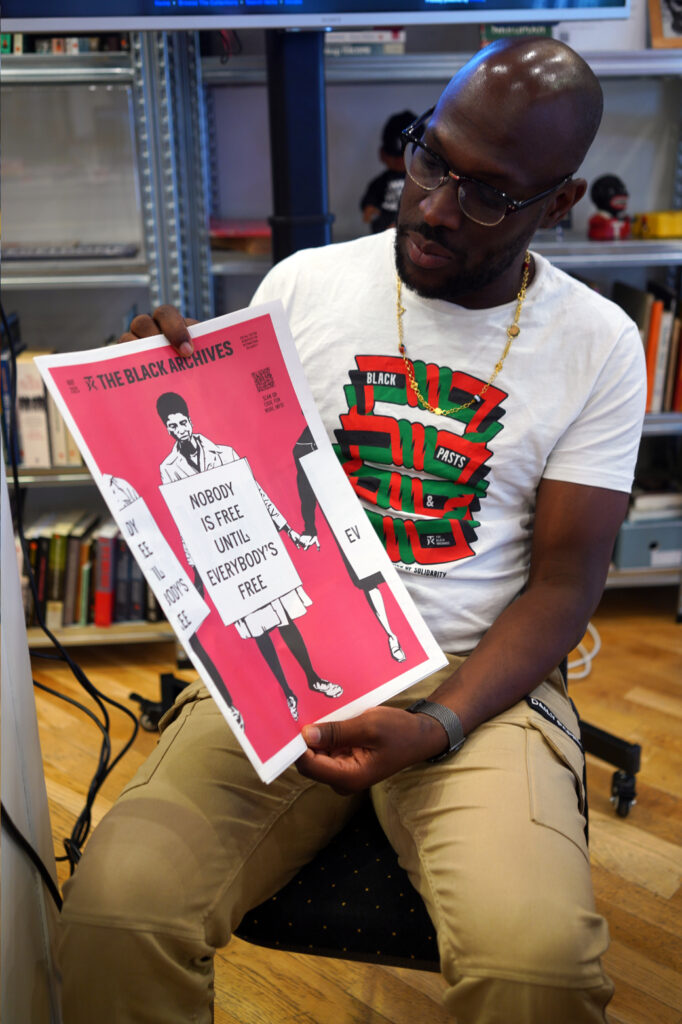

I had a very special surprise at the Black Archive in the south of the city. There I spoke to Mitchell Esajas about Keti Koti. It was a prearranged interview about the bottom-up work of this Amsterdam history workshop, or more precisely, a workshop for postcolonial memory culture, which for years has been collecting all available sources and testimonies of Surinamese and global Black resistance culture and making them accessible to anyone interested.

But we had to wait a little while, because Mitchell was giving a lecture to a large group of traveling European artists. The Black Archive has a fantastic library with books by Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Gloria Wecker, who has greatly advanced postcolonial studies and political debate in Amsterdam, and many, many more from the depths of Black history, which is still largely unknown to most of us. The Black Archives are currently located in Amsterdam Zuidoost, where many immigrants from Suriname live. Coincidentally, the day before, I had seen an exhibition by the Black Archive at the Keti Koti festival grounds in the city center, where numerous portraits of important figures in the Black resistance were on display.

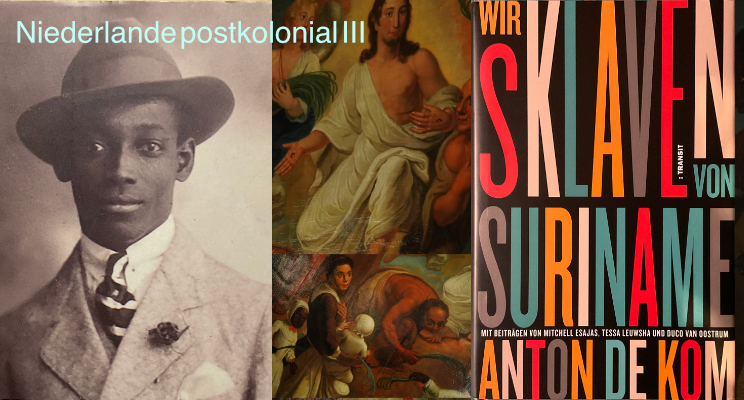

One photo poster in particular caught my eye, showing a young Surinamese man wearing a hat, looking straight into the camera, almost like a young Kafka. I had no idea who he was, but I read the name, Anton De Kom. He was also featured elsewhere on a fabric poster and on a poster with photos and texts. Contacts from my research on the mission had already mentioned his name to me as one of the central sources of Dutch counterhistory. But it was only when I was back in Berlin and continued my research in the usual way that I came across the book „Wir Sklaven von Suriname“ (We Slaves of Suriname) by Anton De Kom, and lo and behold, the accompanying text in the German edition published by :transit Verlag was written by Mitchell Esajas from the Black Archive.

That’s often how things turn out when you do a lot of research, but I admit it’s a bit embarrassing that I’ve only just read this classic work of anticolonial literature. But I have, and it has left a lasting impression on me because I have rarely read such a powerful book on the broad topic of violence in the slave-owning system. Violence is a linchpin of Anton De Kom’s book about the Dutch colonial system in Suriname, as violence was essential to the implementation and maintenance of the entire inhumane colonial system of exploitation, much more so than I had previously known. In principle, my idea of violence on the plantations is shaped by a few particularly brutal descriptions, often found in fiction, and unfortunately one then tends to view these descriptions as isolated incidents, exceptions, but the truth is that they were everyday occurrences, the perverse was the norm, and the continuity of brutality against the enslaved was a prerequisite for the survival of the system.

The colonial system of oppression and the mass extermination of enslaved people are difficult to comprehend, if only in terms of their temporal dimension. For over two centuries, Africans were deported to European colonies, year after year, where they were mercilessly exploited on highly profitable plantations until the end of their mostly short lives, generation after generation. How can we comprehend the suffering that the colonial system inflicted on all these people? Certainly not by continuing to remain silent. This nightmare is history, and history has documents, reports, and images. Anton De Kom knew them.

Anton De Kom’s chronicle of conditions in Suriname contains numerous descriptions of naked violence. I will quote just one here, as it is particularly drastic and concerns the widow of Governor Mauricius.

„The widow Mauricius, a lady from the highest circles of Surinamese society, had an old slave tied to a tree and beaten to death. She herself explained that she had allowed this on a whim because she wanted to see her old servant suffer. Several of her slaves had suffered the same fate, and even the small children on her plantation were often punished with the Spanish rack (a very sophisticated form of torture, which we will discuss later). On another occasion, she declared: „I don’t want any of my Negroes walking around my plantation with such smooth skin.“ And indeed, she had devised an effective cure that rarely failed to have the desired effect. For example, she sometimes had all her slaves flogged continuously for twenty-four hours and „half skinned or flayed.“

The use of the Spanish rack is described several times by Franz De Kom, and with good reason: this punishment was carried out daily, either by the colonists themselves, on street corners, on plantations, or for payment in the coastal fort, where even the hardened soldiers complained about the incessant cries of pain. There is a not entirely unfounded reservation in the postcolonial community that the depiction of sadistic violence in the colonies keeps the racist impulse alive, that the traditional sense of superiority of the oppressors is revitalized when they see images and reports of the atrocities committed by their ancestors.

This may well be true of racists, and unfortunately we are becoming increasingly aware that this scourge of humanity has never really disappeared from Europe. But when I, as a journalist, analyze the successful political maneuvers of a racist party in Denmark and publish my findings in Germany as a warning, I still have to risk that German sympathizers of the Danish racists will misuse my analysis as a populist recipe. But if I don’t report on it, then journalism has failed in its purpose and they can continue and expand their machinations unchecked and uncontrolled. The Link leads to the program, in German:

(As I once read by chance, the Berlin AfD actually undertook an educational trip to the Danish People’s Party. This is not harmless, because they are united in their hatred of foreigners and Islamophobia, which are currently the door openers worldwide for fascist and authoritarian demagogues who always bear the stamp of racism.)

And if the perversions of a woman like Mauricius are concealed—she was not the only one of her kind, and the vast majority of sadists and torturers were, of course, men—then we fail to learn the lesson of history: the descent into this kind of sadism, the unrestrained exercise of total power, is only possible when this personal abuse of power is covered up by ideological conviction and a political infrastructure. There is a Mauricius before she came to power, a respectable governor’s wife with social ambitions who can live out her fantasies of white superiority in salon gossip, but as the mistress of the plantation, she becomes a gruesome fury. Let us beware of the racists of our day and keep them away from power.

The plantation system of European colonialism is history, but it is not as complete as one might think. Colonial power as a consequence of naked violence becomes psychosocially inscribed in the collective subject of oppression, and this process of mental enslavement does not end with the last day of the slavery system in 1863. In the last section of the book, „The Age of Freedom,“ Anton De Kom describes how the exploitative system of unfree labor in the colony was maintained by local companies well into the 20th century. The author himself was born and raised in Paramaribo, was expelled and received his education in Europe, returned when he was about thirty years old, and gained deep insights into the colonial business structures as an accountant.

The author reports on attempts by the Dutch government to develop colonial projects in Suriname with emigrants. But not emigrants who could quickly become rich on the basis of slave labor and never lift a finger themselves, but farmers or forest workers for small, self-sustaining colonial projects. These projects were deliberately sabotaged by the ruling class in Suriname, because where would they be if the enslaved people realized that free people also work? Later, for the formerly enslaved, farm work remained associated with slavery and trauma, and they wanted to escape it.

They wanted to finally be their own masters and would have had the chance to form a functioning middle class as craftsmen and traders, but this was thwarted because the real masters needed, if not slaves, then at least subjugated workers.

According to Anton De Kom, this is the logical legacy of the colonial system: „The N* is a propertyless proletarian who must pay the prices arbitrarily set by the company in this so-called truck system for his food, equipment, and tools.“

This last part of the book confirms once and for all how We, the Slaves of Suriname (originally published in 1934) combines extraordinary literary talent with crystal-clear journalistic precision and a resolute commitment to the working class to produce an exemplary critique of colonial conditions. According to Anton De Kom, the problem does not end with the abolition of slavery, just as drudgery and exploitation did not end for the majority of the descendants of the enslaved in 1863 by decree, and unfortunately, the success story of those who profited from slavery does not end either.

Yacht culture in the Caribbean speaks its own language, but the Dutch descendants of the European plantation and slavery system still enjoy the benefits of capital originally acquired through brutal force, visible in material form in the villas on the Herengracht in Amsterdam, for example. In the symbolic landscape of Amsterdam’s city center, on the other hand, the claim to symbolic supremacy over history continues unabated, glorified in the proudly displayed symbols and artifacts of colonial rule. This rule lasted in Suriname until 1975, and the money is still warm.

Naturally, this is to be kept quiet, and even in a metropolis of European colonialism such as Amsterdam, this has worked quite well.

However, there has been successful resistance to this for some time now, and the postcolonial status quo of colonial amnesia is being successfully challenged today through an admirably diverse range of initiatives. A beautiful symbol of this is Oosterpark, which is dedicated to the memory of those who were enslaved: On one side stands the impressive Keti Koti monument, erected in 2002, and on the other side of the park is the monumental Tropenmuseum, founded in 1864 as a colonial museum in Haarlem, now called the Wereldmuseum, which will continue to host one of the best postcolonial exhibitions in Europe for another four years. May this bottom-up curatorial energy continue to unfold with all its might.

I would like to take this opportunity to remember Anton De Kom, who joined the Dutch resistance against the German occupiers in 1940. His life ended shortly before the defeat of the Nazis, who murdered him in 1945 on the death march from Neuengamme concentration camp to Sandbostel camp.